Construction Of Arbitration Agreement: Ninth Circuit Holds That Agreement To Arbitrate Employment-Related Claims Does Not Include Qui Tam Action Against Employer

Court Ducks Ruling On The Enforceability Of Agreement To Arbitrate False Claims Claims, Saying It Is Only Ruling "On A Rather Unremarkable Textual Analysis."

An interesting issue exists as to whether qui tam claims, brought by a private party (the "relator" or "private attorney general") are arbitrable. The argument against arbitrability is that the qui tam claim (in our next case, a False Claims Act claim) is really brought on behalf of the government, which is not a signatory to the arbitration agreement. The argument in favor of enforcing the arbitration agreement is that the claim is brought and prosecuted by a private party that is a party to the arbitration agreement, and that frequently the government has de minimis involvement in pressing a qui tam claim, leaving the hard lifting to the private party.

As explained by Judge Fisher in United States Ex Rel. Welch v. MLF, No. 16-16070 (9th Cir. Sept. 11, 2017) (Fisher, Schroeder, Smith), the District Court held that, "because FCA claims belong to the government and neither the United States nor Nevada agreed to arbitrate their claims, sending this dispute to arbitration would improperly bind them to an agreement they never signed." The Ninth Circuit panel agreed with the result, but reached it through the route of contract interpretation.

Basically, the Court held that the arbitration provisions covered claims relating to the employment relationship. However, the employee's qui tam claim that her employer was making false Medicaid claims did not arise from the employment relationship, and in fact, could have been brought by a non-employee.

The broadest arbitration provision covered a claim, dispute, or controversy that the employee "may have against [the employer]." As to this broad clause, the Court explained:

Indeed, though the FCA grants the relator the right to bring a FCA claim on the government's behalf, an interest in the outcome of the lawsuit, and the right to conduct the action when the government declines to intervene, our precedent compels the conclusion that the underlying fraud claims asserted in a FCA case belong to the government and not the relator.

The Ninth Circuit affirmed the District Court's denial of the employer's motion to compel arbitration on the alternate ground that the employee's FCA claims did not fall within the scope of the arbitration agreement.

COMMENT: While the Court claims that it is simply engaging in "rather unremarkable textual analysis", is it also setting forth its substantive interpretation of the FCA, namely, that the qui tam claims permitted under the FCA are not claims of the relator, but rather claims of the government? Has the Court through the backdoor of "contract interpretation" admitted the District Court's conclusion that the FCA claim is not arbitrable, because the government holds the claim, but unlike the relator, the government never signed the arbitration agreement? Perhaps the Court's reluctance to take a deep dive into the weeds with a searching discussion of the respective roles played by the relator and the government in pressing the FSA claim in this case explains the Court's choosing the easy way out by following the route of "contract interpretation."

Settlement Agreements: 4/2 CCA Holds Trial Court Can Grant Equitable Remedies In Motion Brought Under CCP Section 664.6 To Enforce Settlement Agreement

Trial Court Erred By Ruling It Could Not Grant Equitable Remedies In Motion Under Section 664.6.

Plaintiff Mathis settled with defendants by agreeing to purchase property from defendants for $1M, with escrow to close in 120 days. The trial court dismissed the underlying case, while retaining jurisdiction under that convenient device, Cal. Code of Civ. Proc., section 664.6, to enforce the settlement. Mathis moved to enforce the settlement agreement asking the trial court to grant equitable relief modifying escrow terms by extending the date of closing, and by assigning the property to a nominee. The trial judge denied the motion, ruling it had no jurisdiction to modify the settlement agreement, and Mathis appealed. Mathis v. Pacific Mortgage Exchange, Inc., et al., E063868 (4/2 9/7/17) (Ramirez, Miller, Slough) (unpublished).

"While this was not an unreasonable reading of the statutory language, it was incorrect under established case law. On a motion to enforce a settlement under section 664.6, a trial court has jurisdiction 'to provide any appropriate equitable remedy,'" explained the Court, relying on Lofton v. Wells Fargo Home Mortgage, 230 Cal.App.4th 1050, 1061-1062 (2014).

Because the trial court has the power to grant equitable relief when enforcing a motion brought under section 664.6, upon remand, the trial judge will have to consider whether it is appropriate to provide the requested relief.

BEST LINE IN THE OPINION: "[D]efendants pick up the scent of Mathis's red herring and run off after it."

Herman Bencke, lithographer. Library of Congress.

Arbitration, Gateway Issues, Delegation: 2/7 CCA Reverses Trial Court’s Order Denying Petition To Compel Arbitration Because Incorporated AAA Rules Delegated The Decision To The Arbitrator

Sixteen Page Majority Decision Draws Fifteen Page Concurrence And Dissent From Justice Segal.

If an agreement to arbitrate is unconscionable, why should decisions about arbitrability ever be sent to the arbitrator? Answer: ordinarily, it is presumed that decisions about arbitrability are to be made by the judge, and therefore a determination that the agreement is unconscionable will not be sent to the arbitrator. And if the judge decides that the arbitration agreement is unconscionable, the arbitrator will never get to decide anything. The exception to this rule, however, is that the parties may agree to delegate to an arbitrator the authority to decide questions of arbitrability — and that can include whether the arbitration agreement is unconscionable.

In Advanced Air Management, Inc. v. Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation, B265723 (2/7 9/6/17) (Menetrez, Zelon; Segal, concurring and dissenting) (unpublished), the trial court held that an agreement between the plaintiff and the defendant was unconscionable. Judge Menetrez, sitting by designation, and Justice Zelon, however, reversed the trial court's order denying Gulfstream's petition to compel arbitration, because the incorporation of AAA Commercial Rules delegated the decision-making authority on the unconscionability issue to the arbitrator. As a result, the arbitrator will get to decide the unconscionability issue.

Justice Segal concurred and dissented. He concurred that the parties agreed to delegate the issue of arbitrability to the arbitrator. However, he would have held that Gulfstream invited error it argued the trial court made in deciding the issue, because Gulfstream asked the court to decide the issue. However, Justice Segal believed that the arbitration provision was not unconscionable.

COMMENT: Apparently Gulfstream did not explicitly reference arbitrability in its petition to compel arbitration. Justice Segal explains that Gulfstream argued that it asked the court to refer arbitrability to the arbitrator "by asking the court to compel Advanced Air to arbitrate the claims raised in its complaint" and that one of the claims raised in Advanced Air's complaint "was that the arbitration clause was unconscionable." Justice Segal then sets forth verbatim the dense language in Advanced Air's complaint, and challenges the reader to find the hook upon which Gulfstream is hanging its argument that it preserved the issue of delegating to arbitration whether the arbitration clause was unconscionable. "Did you miss it?" asks Justice Segal, adding "So did I." Actually, I did not miss it the first time. But thanks to Justice Segal, I was looking for the language on which Gulfstream relied.

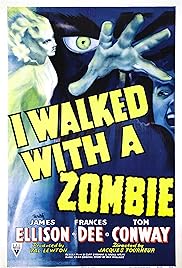

Arbitration, Appealability, Nonsignatories: 9th Circuit Grants Writ, Vacates Order Granting Motion To Stay And To Compel Arbitration Obtained By Alleged Zombie Cookie User

How Do You Like Them Zombie Cookies?

"I walked with a Zombie." 1943.

The Ninth Circuit granted a petition for a writ of mandamus and vacated the district court's order that had granted Turn, Inc.'s motion to stay a putative class action and compel arbitration with Turn, Inc., the alleged user of "zombie" cookies. In re Henson, No. 16-71818 (9th Cir. 9/5/17) (per curiam).

Turn, Inc. is a middle-man for Internet-based advertisements, and has a contract with Verizon to deliver advertisements to Verizon subscribers based on usage data collected from the users' mobile devices. The users' wireless transmissions contain a "Verizon Unique Identifier Header" that can be attached to a tracking cookie to send the user data to Turn, Inc. As the Court explains, "A 'cookie' is software code that transmits a user's web-browsing history and other usage data back to the entity that attached the cookie."

"Subscribers were allegedly unable to detect, delete, or block these 'zombie' cookies attached to their UIDHs." Even when the user tried to kill a zombie cookie, the cookie would be replicated, and attach to the user's previously collected data. Turn, Inc. allegedly auctioned off users' collected data so advertisers could place targeted advertisements on the users' mobile phones. The putative class action alleged deceptive business practices and trespass to chattels by Turn, Inc.

Verizon had an arbitration provision in its user contracts, but Turn, Inc. was not a party to those contracts. Though a nonsignatory, Turn, Inc. sought to take advantage of the arbitration provision, and the district court, applying equitable estoppel, allowed Turn, Inc. to do so, staying the lawsuit and requiring arbitration.

A party cannot directly appeal from an order compelling arbitration, requiring the Court to analyze whether mandamus was available. Applying the so-called Bauman factors, the Court found that the first three weighed in favor of granting mandamus, and granted mandamus. In Bauman v. U.S. dist. Court, 557 F.2d 650 (9th Cir. 1977), the court considered whether a direct appeal is unavailable, whether prejudice is not correctable on appeal, whether clear error exists, whether the error is often repeated, and whether the issue is of first impression.

![[Girl Scout serving cookies]](http://cdn.loc.gov/service/pnp/hec/40200/40244r.jpg)

Girl Scout serving cookies. 1936. Library of Congress.

Arbitration, Class, Waiver, Collective Bargaining: 2/7 CCA Affirms Part Of Order Requiring Arbitration, Grants Part To Deny Arbitration Of Statutory Claims To Pay Wages Timely And For Unlawful Competition, Agrees Class Action Waived

Arbitration Was Required Under A Collective Bargaining Agreement That Did Not Provide For Class Arbitration.

Brushing aside thorny appealability issues, Cortez v. Doty Bros. Equipment Company, B275255 (2/7 filed 8/15, pub. order 9/1/17) (Perluss, Zelon, Segal) treated an employee's appeal as a writ of mandate, enabling the Court to address the effect of an arbitration provision in an employer/union collective bargaining agreement (CBA).

The Court agreed that the arbitration provision in the CBA, requiring the employee to arbitrate claims "arising under" Wage Order 16, showed a clear and unmistakable intent to arbitrate claims relating to Wage Order 16, even if the claims referenced the Labor Code without referencing Wage Order 16. "To hold that wage and hour disputes arising under Wage Order 16 are arbitrable under the CBA only in theory, but not in practice because they are, by necessity, brought under the Labor Code, would result in the very absurdity courts are required to avoid."

Causes of action for statutory penalties due for failure to pay wages timely, and for unfair competition based on the employer's purported violations of the Labor Code, were another matter. Here, the CBA did not contain an explicit and unmistakable agreement to arbitrate those statutory claims. The waiver of the right in a CBA to prosecute a statutory violation in a judicial forum is only effective if it is explicit, "clear and unmistakable." Therefore, those two claims could not be arbitrated.

Finally, the the Court held that the CBA did not contemplate class-wide arbitration — "the CBA refers to the grievance or dispute of an individual employee, not a group of employees."

COMMENT: We have previously blogged about an issue resulting in a split among the US Courts of Appeals, and on the docket at the beginning of the new Supreme Court term: whether waivers of class-wide arbitration violate the NLRA's protection of collective activity. 9th Circuit and 7th Circuit: Yes, that's a violation. 5th Circuit, no, labor organizing does not mean class legal action. See posts dated 10/11/16, 1/17/17, 7/24/17, 8/23/17.

The NLRAs protection of concerted activity is clearly relevant to the outcome in Cortez, and as to the applicability of that protection to class legal activity, the 9th Circuit and the California Supreme Court are not on the same page. Because "'the NLRA's general protection of concerted activity, which makes no reference to class actions,' [Iskanian v. CLS Transportation, LLC Los Angeles, 59 Cal.4t 348, 375-376 (2014)] does not bar parties to a CBA from excluding class claims from the agreement to arbitrate," the Court in Cortez saw no reason to delay and wait for a ruling from the SCOTUS.

Arbitration/Confidentiality: Is Arbitration Confidential?

My Article, "Confidentiality in Arbitration" Is In The Latest Issue of California Litigation And Available Through This Post.

My article on "Confidentiality in Arbitration" and an accompanying MCLE test are published in California Litigation, The Journal of the Litigation Section, State Bar of California, Vol. 30, No. 2 (2017), p. 6. With the permission of the State Bar, I have republished the article and the test, and they are available by clicking here.