Mediation/Confidentiality/In the News: Judge in Stockton Bankruptcy Limits Release of Mediation Information to Public

When Mediation Involves The Public’s Interest, How Confidential Is The Mediation Under Federal Law?

On July 6, 2012, Steven Church reported in Bloomerg, “[t]he judge overseeing Stockton, California’s bankruptcy limited the amount of information the city and its creditors can make public about a months-long mediation process that failed.” Mediation is required under California law before a city can file for bankruptcy. Mr. Church reports that Bankruptcy Judge Christopher Klein ruled that the City’s offer can eventually be made public, but that counter-offers remain confidential. Interestingly, the City asked for release of the information, while bondholders asked for the release of some of the information.

The issue is noteworthy to us, because the confidentiality of mediation-related matters is somewhat unsettled under federal law, though the privilege is strong under California law (Cal. Evid. Code 1119). Thus, we have posted about Facebook, Inc. v. Pacific Northwest Software, Inc, 640 F.3d 1034 (9th Cir. 2011), in which the Court of Appeals Court expressed doubt that the federal district court Local Rules applying to ADR could create a “privilege” for confidential communications in a mediation, because privileges are created by the Federal Rules of Evidence, which rules cannot be overruled by Local Rules. See also Phyllis G. Pollock, Mediation Confidentiality: A Federal Court Oxymoron, The Resolver 8, available at http://www.pgpmediation.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/mediation-confidentiality-a-federal-court-oxymoron31.pdf (urging adoption by the states of the Uniform Mediation Act to create consistency and provide “a framework for the federal courts,” and urging codification of a federal mediation privilege); Joseph Lipps, The Path Toward A Federal Mediation Privilege: Approaches Toward Creating Consistency for a Mediation Privilege in Federal Courts (google the title to find the article).

In The News: Mediation Ends, Stockton Fends

Stockton Goes Bankrupt

On June 28, 2012, Stockton declared bankruptcy. The news story was widely reported.

But all is not gloom and doom. As quoted in the New York Times, bankruptcy attorney Karol K. Denniston, who helped draft AB506, the California legislation requiring municipalities to mediate before filing a bankruptcy petition, optimistically observed: “Despite their failure to reach an agreement, three months of negotiation between the city and its creditors could make the bankruptcy process more efficient by shortening what can otherwise be a long and costly period in court . . . “

Mediations that do not resolve a dispute are frequently judged to be failures. Such a judgment can be premature. Often mediation, even when it does not lead to immediate resolution, creates conditions making a dispute more amenable to future resolution.

We raise another issue related to the financial problems facing cities: pension funds for public employees that are underfunded and unsustainable. Can the pension funds themselves go bankrupt? Not if they are governmental units. Whether the employee’s public pension fund can declare a Ch. 11 bankruptcy is the issue in a pending case in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). Judge Robert J. Faris of the U.S. District Court for the CNMI Bankruptcy Division, who is handling a bankruptcy decision for the public employee’s pension fund in CNMI, recently issued a tentative decision that he was inclined to dismiss the bankruptcy, because the pension fund is a governmental unit. As reported by NPR, “[t]he CNMI may be small, but this case has ramifications for much larger pension funds all across the U.S. that are facing shortfalls.” Regardless of what happens in the CNMI case, one suspects this is not the end of the story.

If public employee pension funds were able to declare bankruptcy, this could be a game-changer that could in turn change the playing field for cities facing bankruptcy.

Caption: “Waiting for the semimonthly relief checks at Calipatria, Imperial Valley, California. Typical story: fifteen years ago they owned farms in Oklahoma. Lost them through foreclosure when cotton prices fell after the war. Became tenants and sharecroppers. With the drought and dust they came West, 1934-1937. Never before left the county where they were born. Now although in California over a year they haven’t been continuously resident in any single county long enough to become a legal resident. Reason: migratory agricultural laborers.” Dorothea Lange, photographer. 1937. Library of Congress.

Mediation/Fees/Condition Precedent: Party Prevailing On Complaint And Cross-Complaint Can Recover Fees On Cross-Complaint Despite Failure To Request Mediation Before Filing Complaint

For Fee Recovery, Complaint And Cross-Complaint Are Treated As Separate Actions

In Frei v. Davey, 124 Cal.App.4th 1506 (2004), the Court of Appeal made it very clear that parties need to pay attention to those pesky provisions requiring that one request mediation before filing suit, or else risk losing attorney’s fees even if one prevails. That’s what happened to the plaintiff, at the trial court level, in Castleton Real Estate & Development, Inc. v. Tai-Fu California Partnership, Case No. G044304 (4th Dist. Div. 3 June 28, 2012) (Rylaarsdam, J., author) (unpublished). The outcome, however, was changed by the appeal.

Plaintiff Castleton sued to recover its broker’s commission, without first requesting mediation. Big problem: the listing agreement required Plaintiff to request mediation before initiating litigation. Defendant Tai-Fu cross-complained, also without requesting mediation. When Castleton then requested mediation, Tai-Fu refused to mediate. Castleton prevailed on both its complaint and on the cross-complaint against it. However, when it requested attorney’s fees from the trial court, it was rebuffed, because it had failed to request mediation, a condition precedent to bringing suit. Castleton appealed.

On appeal, Castleton conceded it could not recover fees for the prosecution of its complaint because it failed to seek mediation prior to filing it. However, Castleton contended it was entitled to fees for its defense against the cross-complaint, as the cross-complaint initiated a separate action. The Court of Appeal agreed: the filing of a cross-complaint “institute[s] a ‘. . . . separate, simultaneous action’” distinct from the initial complaint and makes the cross-defendant a defendant. Bertero v. National General Corp., 13 Cal.3d 43, 51 (1974). The Court remanded the matter to the trial court to determine the appropriate amount of fees to award.

“Half a loaf is better than none.” Flickr Creative Commons License. mystuart’s photostream.

Arbitration/Enforceability: Cal Supreme Court Reverses Judgment To Compel Arbitration To Enforce Collective Bargaining Provisions, But Remands For Further Findings

Supreme Court Faced “Tension Between Two Principles”

In United Teachers of Los Angeles v. Los Angeles Unified School District, S177403 (Cal. Sup. Ct. June 28, 2012) (Liu, J., author), the Supreme Court found itself “required to resolve a tension between two principles: (1) collective bargaining provisions in conflict with the Education Code are unenforceable, and (2) courts generally do not examine the merits of the underlying dispute in deciding whether to enforce arbitration agreements.”

The underlying dispute arose after the LA Unified School District approved the conversion of an existing public school into a charter school, and the UTLA filed grievances that the District failed to comply with provisions of a collective bargaining agreement concerning school charter conversions.

Reversing the trial court, the Court of Appeal had concluded that it was not for the court, on a petition of the UTLA to compel arbitration, to decide whether there was a conflict between the collective bargaining provisions and charter school statutes. The sole function of the Court of Appeal was to determine whether there was a valid arbitration agreement that had not been waived. The Court of Appeal ordered the petition to compel arbitration granted. The Supreme Court reversed the Court of Appeal.

The Supreme Court concluded that the petition to compel arbitration should be denied “if the collective bargaining provisions at issue directly conflict with provisions of the Education Code – that is, if they would annul, replace, or set aside Education Code provisions.” The Supreme Court further held that under the Education Code, “an arbitrator has no authority to deny or revoke a school charter, as UTLA requests.” However, the Supreme Court then remanded the case to the trial court to give the UTLA an opportunity to identify specific provisions which the collective bargaining provisions allegedly violated, because the UTLA had not identified those provisions with sufficient particularity.

NOTE: The case has no discussion, common in cases involving efforts to compel arbitration, of the federal cases involving federal preemption and the Federal Arbitration Act. We assume this is because a charter school conversion may involve entirely local matters that do not involve the Commerce Clause.

Arbitration/Res Judicata/Mediation/Confidentiality/Settlement: Fourth District, Division 3 Offers Interesting Analysis Of Settlement Provision’s Effect On Res Judicata And Mediation Privilege

Settlement Provision Conferred Limited Authority On Arbitrator to Amend Settlement Agreement to Make It Enforceable

A cleverly drafted settlement provision, which had implications for the res judicata effect of an arbitration award, and for the confidentiality of mediation, is the reason this next case earns a blawg post. The underlying dispute was a messy partnership buyout and accounting, complicated by the defendant’s misstatement of his authority to bind a group of real estate businesses to the settlement. (One who signs as an agent can take on liability if authority is lacking). Litigation led to mediation, followed by arbitration, followed by a bifurcated bench/jury trial, followed by cross appeals. Kurtin v. Elieff, Case No. G043999 (4th Dist. Div. 3 June 27, 2012) (Rylaarsdam, Acting P.J., author) (published). The Court of Appeal affirmed most of the trial court’s judgment, with some interesting analysis of a settlement provision resulting from the mediation. (Famed mediator Tony Piazza was involved).

Arbitration/Res Judicata

The settlement resulting from mediation included a clever provision addressing a bedeviling problem – how to efficiently handle settlement enforcement problems resulting from ambiguity:

“The sole act of the arbitrator shall be to issue an amendment to this Settlement Agreement implying such additional terms, curing any ambiguity or otherwise curing any defect in the Settlement Agreement that would make this Settlement Agreement unenforceable.” (italics in the opinion).

Defendant Elieff contended that an arbitration decision that followed the mediation/settlement precluded the subsequent civil court judgment by way of res judicata or collateral estoppel. However, the Court of Appeal rejected that argument, because of how severely the settlement agreement limited the power of the arbitrator. All the arbitrator could do was clear up ambiguity or defects in the settlement agreement to make it enforceable. It followed that the res judicata effect of the arbitrator’s decision was limited.

Mediation/Confidentiality

Defendant Elieff also argued that Kurtin’s invocation of the mediation privilege, which made it impossible to bring in extrinsic evidence from the mediation to interpret the settlement, denied Elieff a fair trial. Once again, however, the settlement agreement provided the answer:

“The mechanism set up by the settlement agreement was one where the parties first would resolve any ambiguities in the contract before going to court. Thus, in asserting the mediation privilege, Kurtin was only following the settlement agreement’s own logic, not sandbagging Elieff.”

Tip: The settlement provision here is one to keep in mind if you are concerned that enforcement of the settlement agreed to in mediation may be difficult because of some unforeseen ambiguity or defect.

Arbitration/Fees/Construction: Fifth District Agrees Attorney’s Fees Clause Provided For Recovery Of Fees Only In Arbitration, Not In Superior Court

Parties’ Agreement To Litigate In Superior Court Proved Fatal To Prevailing Party’s Fee Recovery

Plaintiff Mari sued Defendant Hawkins for professional negligence in connection with a survey, and prevailed in the trial court. However, the trial court denied Plaintiff’s request for attorney’s fees, because the fee provision was part of an arbitration provision stating, “[t]he arbitrator will award attorney’s fees to the prevailing party” — and the parties agreed to proceed in superior court rather than to arbitrate. Mari v. Hawkins, Case No. F062563 (5th Dist. June 25, 2012) (Kane, J., author) (unpublished). Plaintiff appealed the adverse fee ruling.

The contract between the parties contained three separate fee provisions. However, the broadly worded fee provision, quoted above, applied only to arbitration. Plaintiff argued that the provision applied, and the parties simply substituted a judge for an arbitrator. Nope, that didn’t work.

The second fee provision provided, “[i]f any proceeding is brought to enforce or interpret the provisions of this Agreement, the prevailing party therein shall be entitled to receive from the losing party therein, its reasonable attorney’s fees . . . “ Plaintiff ingeniously argued that prevailing on the claim for professional negligence required interpreting the contract. Nope, that didn’t work either. Suing for professional negligence is different than suing to enforce or interpret the provisions of a contract.

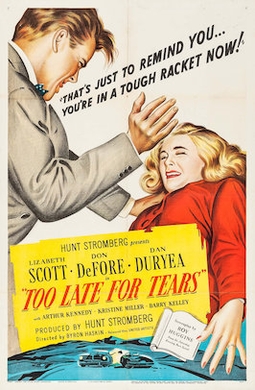

The third fee provision provided, “[i]n the event [plaintiff] institutes a proceeding against [defendants], either directly or by way of cross-complaint, including a claim for . . . alleged negligence . . . wherein [defendants prevail], [plaintiff] agrees to pay [defendants] immediately following the proceedings all costs of defense, including . . . reasonable attorneys’ fees . . . .” Nope, that too didn’t work. The problem here is that the clause is not reciprocal – it provides recovery to a prevailing defendant, but not to a prevailing plaintiff. But I thought attorney’s fees provisions were reciprocal? Well might you ask. Attorney’s fees provisions are reciprocal when the action is on a contract (Civ. Code section 1717). Here, you will recall that Plaintiff prevailed on a cause for professional negligence, not for breach of contract. Therefore, the third provision is valid, despite the fact that it is not reciprocal. However, because that fee provision is not reciprocal, the prevailing Plaintiff derived no benefit from it here. Too late for tears . . . .

The order of the trial court was affirmed.

Comment: Consider the economics of this case. The parties went to trial, filed post-trial briefs, and went through an appeal. At trial, Plaintiff was found to be damaged in the amount of $155,134, but the damage amount was reduced by the trial judge to $50,000, due to a contractual fee limitation. Then, because the parties had agreed to litigate in superior court, Plaintiff was denied fees. The opinion does not tell us how much the fees were, but you can guess.

Practice Tip: When confronted with a choice of an arbitral or judicial forum, consider the fee implications. Also, consider whether agreeing to litigate in one forum rather than another forum means the attorney’s fees provisions ought to be revisited and revised.