Arbitration/Enforceability: Cal Supreme Court Reverses Judgment To Compel Arbitration To Enforce Collective Bargaining Provisions, But Remands For Further Findings

Supreme Court Faced “Tension Between Two Principles”

In United Teachers of Los Angeles v. Los Angeles Unified School District, S177403 (Cal. Sup. Ct. June 28, 2012) (Liu, J., author), the Supreme Court found itself “required to resolve a tension between two principles: (1) collective bargaining provisions in conflict with the Education Code are unenforceable, and (2) courts generally do not examine the merits of the underlying dispute in deciding whether to enforce arbitration agreements.”

The underlying dispute arose after the LA Unified School District approved the conversion of an existing public school into a charter school, and the UTLA filed grievances that the District failed to comply with provisions of a collective bargaining agreement concerning school charter conversions.

Reversing the trial court, the Court of Appeal had concluded that it was not for the court, on a petition of the UTLA to compel arbitration, to decide whether there was a conflict between the collective bargaining provisions and charter school statutes. The sole function of the Court of Appeal was to determine whether there was a valid arbitration agreement that had not been waived. The Court of Appeal ordered the petition to compel arbitration granted. The Supreme Court reversed the Court of Appeal.

The Supreme Court concluded that the petition to compel arbitration should be denied “if the collective bargaining provisions at issue directly conflict with provisions of the Education Code – that is, if they would annul, replace, or set aside Education Code provisions.” The Supreme Court further held that under the Education Code, “an arbitrator has no authority to deny or revoke a school charter, as UTLA requests.” However, the Supreme Court then remanded the case to the trial court to give the UTLA an opportunity to identify specific provisions which the collective bargaining provisions allegedly violated, because the UTLA had not identified those provisions with sufficient particularity.

NOTE: The case has no discussion, common in cases involving efforts to compel arbitration, of the federal cases involving federal preemption and the Federal Arbitration Act. We assume this is because a charter school conversion may involve entirely local matters that do not involve the Commerce Clause.

Arbitration/Res Judicata/Mediation/Confidentiality/Settlement: Fourth District, Division 3 Offers Interesting Analysis Of Settlement Provision’s Effect On Res Judicata And Mediation Privilege

Settlement Provision Conferred Limited Authority On Arbitrator to Amend Settlement Agreement to Make It Enforceable

A cleverly drafted settlement provision, which had implications for the res judicata effect of an arbitration award, and for the confidentiality of mediation, is the reason this next case earns a blawg post. The underlying dispute was a messy partnership buyout and accounting, complicated by the defendant’s misstatement of his authority to bind a group of real estate businesses to the settlement. (One who signs as an agent can take on liability if authority is lacking). Litigation led to mediation, followed by arbitration, followed by a bifurcated bench/jury trial, followed by cross appeals. Kurtin v. Elieff, Case No. G043999 (4th Dist. Div. 3 June 27, 2012) (Rylaarsdam, Acting P.J., author) (published). The Court of Appeal affirmed most of the trial court’s judgment, with some interesting analysis of a settlement provision resulting from the mediation. (Famed mediator Tony Piazza was involved).

Arbitration/Res Judicata

The settlement resulting from mediation included a clever provision addressing a bedeviling problem – how to efficiently handle settlement enforcement problems resulting from ambiguity:

“The sole act of the arbitrator shall be to issue an amendment to this Settlement Agreement implying such additional terms, curing any ambiguity or otherwise curing any defect in the Settlement Agreement that would make this Settlement Agreement unenforceable.” (italics in the opinion).

Defendant Elieff contended that an arbitration decision that followed the mediation/settlement precluded the subsequent civil court judgment by way of res judicata or collateral estoppel. However, the Court of Appeal rejected that argument, because of how severely the settlement agreement limited the power of the arbitrator. All the arbitrator could do was clear up ambiguity or defects in the settlement agreement to make it enforceable. It followed that the res judicata effect of the arbitrator’s decision was limited.

Mediation/Confidentiality

Defendant Elieff also argued that Kurtin’s invocation of the mediation privilege, which made it impossible to bring in extrinsic evidence from the mediation to interpret the settlement, denied Elieff a fair trial. Once again, however, the settlement agreement provided the answer:

“The mechanism set up by the settlement agreement was one where the parties first would resolve any ambiguities in the contract before going to court. Thus, in asserting the mediation privilege, Kurtin was only following the settlement agreement’s own logic, not sandbagging Elieff.”

Tip: The settlement provision here is one to keep in mind if you are concerned that enforcement of the settlement agreed to in mediation may be difficult because of some unforeseen ambiguity or defect.

Arbitration/Fees/Construction: Fifth District Agrees Attorney’s Fees Clause Provided For Recovery Of Fees Only In Arbitration, Not In Superior Court

Parties’ Agreement To Litigate In Superior Court Proved Fatal To Prevailing Party’s Fee Recovery

Plaintiff Mari sued Defendant Hawkins for professional negligence in connection with a survey, and prevailed in the trial court. However, the trial court denied Plaintiff’s request for attorney’s fees, because the fee provision was part of an arbitration provision stating, “[t]he arbitrator will award attorney’s fees to the prevailing party” — and the parties agreed to proceed in superior court rather than to arbitrate. Mari v. Hawkins, Case No. F062563 (5th Dist. June 25, 2012) (Kane, J., author) (unpublished). Plaintiff appealed the adverse fee ruling.

The contract between the parties contained three separate fee provisions. However, the broadly worded fee provision, quoted above, applied only to arbitration. Plaintiff argued that the provision applied, and the parties simply substituted a judge for an arbitrator. Nope, that didn’t work.

The second fee provision provided, “[i]f any proceeding is brought to enforce or interpret the provisions of this Agreement, the prevailing party therein shall be entitled to receive from the losing party therein, its reasonable attorney’s fees . . . “ Plaintiff ingeniously argued that prevailing on the claim for professional negligence required interpreting the contract. Nope, that didn’t work either. Suing for professional negligence is different than suing to enforce or interpret the provisions of a contract.

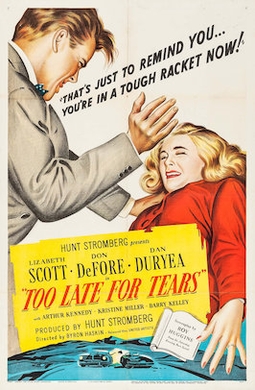

The third fee provision provided, “[i]n the event [plaintiff] institutes a proceeding against [defendants], either directly or by way of cross-complaint, including a claim for . . . alleged negligence . . . wherein [defendants prevail], [plaintiff] agrees to pay [defendants] immediately following the proceedings all costs of defense, including . . . reasonable attorneys’ fees . . . .” Nope, that too didn’t work. The problem here is that the clause is not reciprocal – it provides recovery to a prevailing defendant, but not to a prevailing plaintiff. But I thought attorney’s fees provisions were reciprocal? Well might you ask. Attorney’s fees provisions are reciprocal when the action is on a contract (Civ. Code section 1717). Here, you will recall that Plaintiff prevailed on a cause for professional negligence, not for breach of contract. Therefore, the third provision is valid, despite the fact that it is not reciprocal. However, because that fee provision is not reciprocal, the prevailing Plaintiff derived no benefit from it here. Too late for tears . . . .

The order of the trial court was affirmed.

Comment: Consider the economics of this case. The parties went to trial, filed post-trial briefs, and went through an appeal. At trial, Plaintiff was found to be damaged in the amount of $155,134, but the damage amount was reduced by the trial judge to $50,000, due to a contractual fee limitation. Then, because the parties had agreed to litigate in superior court, Plaintiff was denied fees. The opinion does not tell us how much the fees were, but you can guess.

Practice Tip: When confronted with a choice of an arbitral or judicial forum, consider the fee implications. Also, consider whether agreeing to litigate in one forum rather than another forum means the attorney’s fees provisions ought to be revisited and revised.

Marc Alexander

Marc Alexander is of counsel in the Santa Ana office of AlvaradoSmith APC, and a member of the Firm’s litigation department. He has over 30 years of experience in bench and jury trials, binding arbitrations, judicial references, mediations, and appellate work in state and federal courts in California.

Mr. Alexander received his B.A. with honors from the University of California, Santa Cruz. He received an M.A. and a Ph.D. in history from Johns Hopkins, and he is a member of Phi Beta Kappa. Mr. Alexander received his Juris Doctor degree from UCLA in 1981, and has been licensed to practice law continuously in California since 1981. Upon graduating from law school, he clerked on the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit with the Hon. Warren J. Ferguson.

After clerking for the federal court, Mr. Alexander practiced in California as a litigator with Irell and Manella in its Century City and Orange County offices. In 1986, he joined the litigation department at McKittrick, Jackson, DeMarco & Peckenpaugh in Orange County, California. Mr. Alexander was a shareholder in the litigation department at McKittrick, Jackson, DeMarco & Peckenpaugh; Jackson, DeMarco & Peckenpaugh; Jackson, DeMarco, Tidus & Peckenpaugh; and, Jackson, DeMarco, Tidus, Petersen & Peckenpaugh, until 2008.

Mr. Alexander has broad experience in business and real estate litigation. His experience encompasses landlord-tenant disputes, foreclosures, purchase and sale disputes, title disputes, homeowner association disputes; unfair competition disputes, including non-compete and non-solicitation disputes; partnership and corporate disputes; securities defense; and, intellectual property disputes.

Mr. Alexander is a mediator on the panel for the United States District Court, Central District of California, and a mediator on the panel for the Superior Court of the County of Orange, California.

Over the years, Mr. Alexander has written a number of articles and book reviews on legal subjects. A sampling of his articles includes: Can Private Attorney General Actions Be Forced Into Litigation?, California Litigation, Vol. 28, No. 2, 2015; Summary Contempt and Due Process: England, 1631, California, 1888,” California Litigation, Vol. 27, No. 3 2014; When The American Rule Doesn’t Apply: Attorney’s Fees As Damages In Litigation, California Litigation, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2008 (co-authored with William M. Hensley), Peril of Private Justice: Suspension of Proceedings, Orange County Lawyer, September 2004, Trespass to Chattel and Unsolicited Bulk Email, Orange County Lawyer, September 2003, Protecting Views With Municipal Ordinances, California Land Use, April, 2001, A Newsperson’s Shield Law: A Primer, Civil Litigation Reporter, August, 1995, Despicable Conduct, Or How Punitives Have Been Damaged, Orange County Lawyer, April, 1988, Software Patents and The On-Sale Bar, The Computer Lawyer, January, 1988, When Can An Attorney Contact The Employee Of A Party Represented By Counsel? — Bright Line And Multi-Factor Approaches, Civil Litigation Reporter, December, 1987, When Is A Software Program “Made For Hire?”, The Computer Lawyer, September, 1986, Discretionary Power To Impound And Destroy Infringing Articles: An Historical Perspective, Journal Of The Copyright Society Of The USA (1980).

Mr. Alexander is a co-creator and contributor, with his long-time colleague Mike Hensley, to CalAttorneysFees, a blawg about the law of attorney’s fees in California.

Mr. Alexander is married and has three grown children. He also has a dog named Watson.

Mr. Alexander is available for mediation and arbitration services, and can be contacted by email:

or by telephone:

714.852.6800

or by snail mail:

Marc Alexander

AlvaradoSmith APC

1 MacArthur Place, Suite 200

Santa Ana, CA 92707

Contact Me

Email: calmediation@gmail.com

Telephone: 714 852-6800

Marc Alexander

In the News: $5M Award In FINRA Arbitration, $21.6M Award in JAMS Arbitration

Are Arbitrators Stingier Than Trial Court Judges?

Payback in FINRA Arbitration

Bill Singer comments about a FINRA (Financial Industry Regulatory Authority) arbitration in the June 20, 2012 on-line edition of Forbes, under the heading, “Former Morgan Stanley Smith Barney Brokers Win $5 Million Employment Dispute Arbitration Award.” We surmise some of the conduct may have occurred in California, because the Respondent was also ordered to pay $354,816.54 in attorneys’ fees pursuant to California Civil Code Section 1717 (contract provides for fees to party prevailing on contract cause of action).

Both Sides Declare Victory in JAMS Arbitration

In another arbitration, JAMS awarded the Marin General Hospital Corporation $21.6 million in a dispute with Sutter Health, and $721,000 to Sutter Health. Evidently Marin General Hospital Corporation’s claims were larger still, for both sides are reported to declare themselves pleased with the outcome. So reports the June 20, 2012 edition of the San Anselmo-FairfaxPatch.

The arbitrator was retired Judge Rebecca Westerfield.